Articles liés à The Leopard Hat: A Daughter's Story

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

In my mother's address book, though, a treasurebook filled with her musical handwriting, it is still there, impossible to find unless you know to turn to "Beautyparlor"–the way you can't get the number for the drugstore, the garage, the carpenter, the curtain store, unless you look under "Pharmacy," "Parking," "Handyman," "Draperies." My mother, speaker of nine languages, has her own way of saying things, which I unconsciously adopt. Later my sister and I will cherish these linguistic oddities, the way we always get an adage just slightly wrong–Will wonders never seize!, my mother writes to me my sophomore year in college–and will jokingly refer to it as European Mother Syndrome. But for now friends tease me because I say "valise" instead of "suitcase," or they try to imitate her French accent when she calls for me or my sister from the other end of the apartment, Valérie! Stéphanie! It is always urgent when she calls us, she has to tell us something, wants us to do something right away. She is a woman of the moment.

The beauty parlor is called Davir. I can hear my mother say it, her resonant voice bearing down on the "eeer." We don't have to cross the street to get there. It's right on our block, and like our apartment, it, too, is on the second floor, which is low enough for my mother, who has a fear of heights. Walking into the peach enclave, its floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Madison Avenue, one is quickly embraced by the pungent blend of hair spray and nail polish remover, laced with an assortment of women's perfumes, the barest trace of men's sweat. Under the spinning chairs, there are mouselike heaps of dead hair on the floor, which are continually swept away. Aside from the hairdressers, there are no men, only women, those who want to become more beautiful and those who are there to help them do so. The clients don't look so attractive for the duration of their visit, all of them in the same regulation pink robe, their hair pasted to their heads with various kinds of foul-smelling substances, their makeup causing them to appear a little sad under the bright lights, like clowns.

My mother has to come because she can't do her own hair. She can't do ours either, and tells us from an early age not to be afraid of doing it ourselves. As a result we can do anything–Swedish braids, ballerina buns, high ponytails, our small fingers clicking at high speeds. At home my mother takes baths, not showers, careful not to get her hair wet. She puts oil in the water, and we visit her, washing her back with a soapy wet cloth, dragging it pleasurably over the right angles of her shoulders, the jutting knobs of her hidden spine. Her skin is lustrous, warm to the touch. The water as she leans forward beads off her skin quickly and obediently. Her back is wide and even, browned from years of sun, a gorgeous back. When she wears a backless dress, people take notice. She is a real woman, full of curves, with floating breasts, sunken hips, a tiny waist. I am much narrower on top and bottom, yet my waist will never be as small as hers. I love her body, her back, her arms. We have a game. When I rest my hand on her arm, she tenses it quickly, an invisible flash, her secret way of saying "I love you," which I understand as clearly as if she had breathed the words directly in my ear. At the same time, I see too much of her body, it embarrasses me. She often walks around the house nude, comfortable that way. Eventually we get used to it, thinking that other mothers must be doing the same thing. We figure it is what women do, like wearing a garter belt and stockings.

At the beauty parlor, they wash your hair for you, your head craned back into a sink, one of the women kneading her knuckles into your scalp, a bit roughly, then rinsing the tension away. Sometimes when I arrive, my mother is under a dryer. It reminds me of the painting that hangs in our library, the one my mother's decorator gave to her as a gift after he finished working with her on our apartment. All reds and pinks, it shows a nineteen-forties-era beauty parlor, lipsticked women in strappy shoes and splashy skirts half hidden under ivory-colored casques, lolling about in their chairs as graceful as gazelles. But my mother looks a little funny wearing a robe outside the house, sitting beneath one of the large, smooth, egg-shaped domes, the heat blasting her hair dry and surrounding her with noise. I can't talk to her when she's under there. She'll try to ask me a question–"How was school? How did ballet go?–but no matter what I say she can't hear. One time my mother realized that Grace Kelly was beside her, sitting under the next dryer. The princess leaned over and asked my mother if she could borrow her newspaper. My mother had gone through it already, leaving the pages crumpled and mismatched. "My husband usually insists on reading the paper first," my mother explained ruefully, as she handed over the bedraggled jumble. "Yes, I can see why," the princess replied, with a smile.

My mother's hairdresser, Norberto, is a handsome man. He is permanently tanned, his movements with the comb languorous. We can tell he gets a kick out of my mother, her personality, her stories. As she talks, he grins, teeth flashing, like the gold chain at his open neck. Before he can get to work, he must perm my mother's hair, which is naturally flat. When she was little, her father became obsessed with the goal of changing his daughter's straight locks. He kept insisting that if she shaved her head completely, her hair was bound to grow back in wondrous curls. My mother laughs whenever she tells us this, maybe in relief that it remained just talk, that he never made her actually do it.

Once her head is a mass of ringlets, Norberto does one of two things, depending on the mood she's in. Either her hair goes up, teased into a seductive pile of curls on top of her head and held with pins and a couple of well-placed combs, or down, a more "natural" style, with spray-stiffened waves softly reaching to her shoulders. Whichever one she picks, when she gets home that day and looks in the mirror, she likes it better than the way she had it before. If it's up, she gets mad at us for having liked it down, why were we trying to keep her away from her true look. If it's down, she says we must have wanted her to look old by having it up all the time, it's "younger" this way. She is not really mad, though, just reasoning out loud.

I myself prefer it up. This is what I'm used to, how I think of her, the curls when she first comes home so perfectly arranged. No other mother I have ever seen has her hair that way. As the hours wear on, after the first night of sleeping on it, the upsweep becomes a little lopsided, my mother adding combs and bobby pins haphazardly to keep it upright. She's less coiffed, but maybe more charming that second day. By the third morning, the curls are quite matted down, my mother vainly pulling at them to make them come back to life. No matter what she tries to do, her hair resists her, as if it senses that this is an area where she is not in control. This is why she loves hats. Placing one right on top of her now collapsed do, she is ready–for lunch, for walking up Madison Avenue, for her next appointment at the beauty parlor.

After a hat day, my mother's hair sticks closely to her head, like a little cap. In her bathrobe, she hugs us, her face slick with moisturizer. This is her private side, not the one of lunches at Le Relais with the girls, dinners out with my father. Hair in disarray, pins protruding in odd ways, this is when she organizes our lives, scheduling doctors' appointments, planning trips, keeping up with her family in Belgium. No one else sees her this way. She is ours, not "on." This is how she keeps the whole thing moving, and somewhere here I learn that you can't work unless you're willing to get down and dirty. On a trip with my father, my mother once walked with a friend, talking about the dinner party she was hosting the night after they got back to New York. "How do you do it, Gisèle?" her friend asked, marveling at the abundance of plans. My mother answered right away. "With this," she said, raising up her right pointer finger, her dialing finger, revealing her favored mode of making things happen.

My mother's hands are very shapely. She has square palms, long, elegant fingers, gently curving nails. Her two aunts, my tantes, instruct me from an early age on how nails are supposed to grow, with a roundness from side to side as well as a small curve as the nail leaves the tip of the finger. My nails will never curve as well as theirs–”perhaps it's the American air. My mother gets her nails done at the beauty parlor, although in a pinch she will do her hands herself. She always wears the same color, a bright red, so that I almost don't recognize her hands on the few occasions I see them bare. She gestures a lot as she talks, her cherry-tipped fingers moving about like wands, enhancing every story.

My mother's toes are different. From childhood her mother made her wear too-small shoes, to be ladylike. (When my mother married my father, he encouraged her to buy larger shoes, so her feet wouldn't hurt her all the time. Overnight, she went from a six to a seven and a half.) After her painful experiences, she is very vigilant about making sure that my sister's and my toes have enough room in our shoes. My tantes, come to New York from Antwerp on a short visit, gaze with disapproval at the sneakers we wear all the time. It is summer, we are out in our country house on Long Island running around. They cluck and say that our feet will spread in those sneakers, just get bigger and bigger without any proper leather to keep them reined in. We are glad to wear sneakers, scared that our feet will turn out like our mother's, which are highly sensitive and have strange contours. Her toes overlap, coming together even without shoes to a kind of point. When she gets a pedicure, she makes sure to tell the woman to be careful, it hurts to have her toes manipulated too much. We can't tell whether her toes are misshapen as a result of wearing shoes that are too tight for her, or because she inherited them–" her mother's toes, my tantes' toes, are all in the same condition. Growing up, we will constantly look down to check that our toes are straight, praying for them to stay that way and not start to cross over one another. But they never do, so we learn that the plight was environmental, not genetic.

According to my mother, it's good for you to wear shoes of different heights, but she herself wears only high heels, including the satin slippers in which she traipses around the house. After years and years of nothing but high-heel wearing, her hips have been realigned. Anything flat makes her whole body hurt. A woman who was once on a sailing trip with her was amazed to see that even my mother's canvas boat shoes had a small heel. "But do you always wear high heels?" the friend asked my mother with disbelief. "Always," my mother said. "What about at night?" her friend asked, trying to trip her up. My mother thought about it for a moment, and then answered, "I kick them off!"

From the tips of her toes to the crown of her head, my mother gets dressed as if it were a military operation, every detail fine-tuned to ensure a successful mission. But the final ensemble is not a protective shield or a weapon. It just instinctively becomes part of the way she disarms people, wins them over with her warmth, her charm. She has the European habit of wearing the same outfit several days in a row, especially if it is new or she feels particularly good in it. We have to remind her she is in America, where people wear something different every day.

There is a huge contrast between my mother, fitted out in her finery, and the fury of activity that precedes any outing. The whole house is in a fracas until she finishes getting dressed, especially if it is night and she is going out with my father. (Once, when they were off to the theater, she was in such a hurry that she forgot to bring their tickets, and offered up her diamond earrings for the evening to the man at the box office as proof she wasn't lying.) After her bath, she sits on her bed, pulling on her stockings, demanding her silver-tipped shoes, her beaded handbag, a glass of club soda from the kitchen. She is quick-tempered. My sister and I, the housekeeper, all scurry about, trying to keep up with her impatience. We are allowed to vote on what she's wearing, putting in a plea for a certain bracelet, shoes whose shape or color we feel will work better than the ones she has out. As we grow older, she listens to our suggestions more and more. My sister and I learn how an outfit is constructed, the disparate pieces fitting together just so until she is no longer a woman but a vision. We watch in the bathroom as she blackens her lashes, applies different lipsticks, one on top of the next, until she hits on her own inimitable shade of red. My father has safely removed himself to the library by this point, where we hear him fooling around on the piano, waiting for her. He plays one of several standards, ranging from his and my mother's song, "All of Me," to his own anthem, "The Sunny Side of the Street." The minute my mother's ready, jewels and eyes sparkling, an invisible garland of perfume sparking the air around her, she goes and stands in the library door. "What are you doing, Jerry?" she asks. "We have to leave, we're late." My father, laughing a little because he's been ready all along, puts an early end to his song and stands up to join her. It is a sight we are used to, him handsome in his hat, her enveloped in one of her furs, their attention already out the door, my parents, dressed up and going out for the evening. Then they're gone, the scent of my mother's Opium lingering in the foyer air.

We are not the only ones to notice how regularly she glitters. On March 8, 1983, two men with pistols break into our apartment. They don't even break in, they just put a gun to our superintendent's head and have him ring our back door. They know exactly where they want to go. When our housekeeper asks who it is and then hears the super's voice, she lets them in. It is 9 a.m. on a Tuesday morning. My sister and I are at school. My father is at work. The two men tie up the housekeeper, the super, the back elevator man. They tie up my mother. For shackles they use a motley selection of belts, busting into my closet and grabbing them from where they hang neatly on brass hooks. We will throw them all out afterward, disgusted, the innocent pink grosgrain become tainted, the rainbow stripes no longer happy to the eye.

My mother tries not to tell the men where she keeps her jewelry. She tries to pretend that whatever they see, that's all there is. But they know better. They put a gun to her head and say, We don't want to hurt you, Mrs. Steiker. We're only doing our job. She gives in. A few things are at the bank, in a safe-deposit box, ...

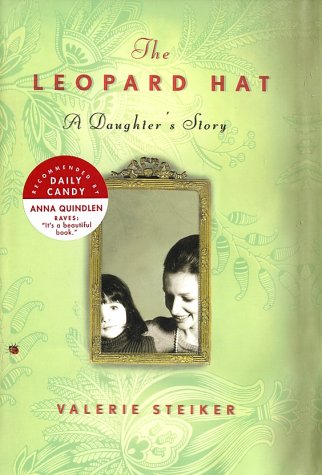

“Poignant. . . . a graceful tracing of her mother's life." —Vogue

“Such a beautiful book. . . . It’s about what home means to you and how it can really be embodied in one person who shapes your life, and how to deal with it after that person is gone.” --Anna Quindlen on the Today Show

“Lovely. . . . Vibrant. . . Gisele sought beauty and loved extravagance in a way that made her the most unforgettable character in her daugther’s life. . . . Remind[s] you of Life Is Beautiful.” —San Francisco Chronicle

"Extraordinary. . . . She titles each chapter of her elegantly structured work after an animal or an insect, then subtly and seamlessly weaves metaphors of anthropomorphism into her narrative, as if into a web." —Newsday

“Here Steiker proves the mother-daughter relationship does not have to be fraught with trouble to be memorable.” —Boston Herald

“Poignant. . . . Quite beautiful. . . . A graceful tracing of her mother's life." —Vogue

“Delicious. . . . Don’t be too surprised if you find yourself rereading passages just to enjoy Steiker’s lush prose, rich descriptions, and above all the talent for living she inherited from her mother.” —Bookreporter.com

“Valerie Steiker combines style and substance in The Leopard Hat, an ode to her flamboyant and sophisticated mother, Gisele.” —Time Out New York

“An outstandingly moving valentine to [Steiker’s] dashing and exuberant Belgian mother... What an incredible family album.” —Daily Candy

“Completely charming .... Can there be any loving daughter who won’t see something of her mother in this memoir, or many readers who won’t be taken by its special mixture of the high-hearted and the heartbreaking?” —Adam Gopnik

“A luminously written debut. . . . A loving tribute to a woman who taught her daughters to value beauty and joy.” —Kirkus

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPantheon Books

- Date d'édition2002

- ISBN 10 0375421017

- ISBN 13 9780375421013

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages326

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,95

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Leopard Hat: A Daughter's Story

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur M8-6-40BH

The Leopard Hat: A Daughter's Story

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks72540

THE LEOPARD HAT: A DAUGHTER'S ST

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.1. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0375421017