Articles liés à New Gilded Age: The New Yorker Looks at the Culture...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

THE CONNECTOR

by LARISSA MacFARQUHAR

Certain people are so uncannily familiar that they seem less individuals than manifestations of a type. Jason McCabe Calacanis-twenty-eight years old, part Greek, part Irish, a native of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn-is one such person. He’s the buoyant carnival barker with big ideas about vaudeville, the teen-age huckster in the trainer mustache and the cheap suit, filibustering his way into a fat cat’s office with plans for a railroad. In his current incarnation, Calacanis is the founder of a miniature media empire that began, three years ago, with the Silicon Alley Reporter, a monthly magazine covering New York’s Internet industry-which is known as Silicon Alley-and has since added a daily E-mail version, a Los Angeles version (the Digital Coast Reporter), and a series of conferences. He has a refined sense of the mechanics of status and display, and has not only climbed nearly to the top of Silicon Alley’s social ladder but crafted many of its rungs. He knows what he wants, and he expresses it with a disarming absence of guile or doubt. “I don’t see why I can’t be the next Michael Eisner or Barry Diller,” he says cheerfully. “Someone has to be.”

Calacanis descended upon Silicon Alley in 1996 like Warhol upon a Brillo factory. Where the world saw twenty-five-year-olds in T-shirts fiddling unprofitably with monotonous graphic effects, Calacanis saw twenty-eight-year-old C.E.O.s with initial public offerings and Palm Pilots. He saw a time when New York content companies would make Silicon Valley technology look dull-“just plumbing.” He saw glamour and money. But it wasn’t money that drew him, or the Internet per se, so much as the scent of something big. These twenty-five-year-olds, he was convinced, were going to change the world, and he wanted to be one of them. Or, rather, he wanted to be their consigliere. He wanted to be the insider’s insider: the one who knew everyone, who dropped hints and joined hands, who sensed what was happening before anyone else. He wanted to tell Silicon Alley what to make of itself, and to tell the world what to make of Silicon Alley. He wanted to be first on the bus to the future.

As one after another of the erstwhile twenty-five-year-olds takes his company public and becomes a multimillionaire, Calacanis likes to remark on the way in which Silicon Alley is taken seriously by Wall Street and ponder the small but noticeable role that he-his magazines, his conferences, the dinner parties he held and the introductions he arranged-has played in bringing it all about. He has discovered, too, to his delight, that his boat has risen with the tide, and the world is looking at him differently. What used to sound like callow cheerleading now sounds like daring realism. “Last winter, I spoke to the Harvard Business School,” Calacanis recalls. “Now, I would never get admitted to that school, except maybe to work in the cafeteria-I got 1150 on my S.A.T.s. But I got to speak to the whole class here in New York, and I told them, ‘I have one piece of advice for you: quit. Leave school tomorrow, take whatever money you have left that you would have spent on tuition, and start an Internet company. Because if you stay in school for the next two years-if, when everybody else is dreaming and innovating, you spend time on the bench, watching the game go by-you’ll miss the greatest land grab, the greatest gold rush of all time, and you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.’ You should have seen the look on their faces: they were terrified. And you know why? Because they knew I was right.”

Calacanis is muscular and compact, and this, along with the tight fit of his clothing and the vivid pinks of his face, gives the impression that he has been shrunk. Perhaps because of his long training in martial arts (he is a fourth-degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do), his movements are curiously orthodox, like those of an action figure. He is not one to lounge or flail about. When he is holding forth on some recent triumph or on the future, his face shines with the manic glee of the last uncaptured child in a game of tag.

One recent morning, Calacanis had scheduled an editorial meeting for nine o’clock. At nine-forty-five, he erupted from the elevator and strode into the Reporter’s offices, on Union Square, leading Toro, his corpulent bulldog, by a leash. Although spiritually Calacanis is committed to staying two steps ahead of the curve, in his daily activities he is invariably late. He had an interview scheduled later that day with Fernando Espuelas, the C.E.O. of StarMedia-the most prominent Spanish-and-Portuguese-language Internet media company-and he had dressed up for the occasion: tight black trousers, thin black dress shoes, a gray jacket that might have been part of a suit. Next to Calacanis’s desk is Toro’s cage, surrounded by the detritus of canine ennui-a shredded tennis ball, a soggy artificial bone. Behind his chair, two larger-than-human cardboard figures from “Star Wars” stand at attention: Darth Vader and an obscure galactic bounty hunter named Boba Fett. Boba Fett has only four lines in all the “Star Wars” movies, but he is the insider’s “Star Wars” character.

The editorial staff of the Silicon Alley Reporter consists of eight people, seven of whom were present that morning. With the exception of Karol Martesko, the magazine’s publisher, no one appeared to be over twenty-five; two interns-one large, one very small-looked as though they had yet to enter high school. Still, the Reporter had come a long way since its inauguration, in the fall of 1996, having expanded from a sixteen-page photocopy to a two-hundred-page glossy magazine. (Calacanis claims that he has had “many offers” to buy the magazine. Asked about rumors that one such offer, worth several million dollars, was made by Jann Wenner, he confirmed that he had met with Wenner, but he declined to say more. “These relationships are like dating,” he says. “It’s not classy to talk about the details.”) Calacanis called the meeting to order. First on the agenda was the next issue’s cover, which was turning out to be something of a problem. People kept backing out, and the current option was not entirely satisfactory. “She doesn’t have a job,” Calacanis said. “It would be kind of weird to put an unemployed person on the cover.”

“Let’s stick with our original mission,” Martesko suggested, with an evil smile. “Let’s make her a star.” In its early days, the Reporter endeared itself to its constituency by according celebrity treatment to Silicon Alley’s would-be entrepreneurs, putting them on the cover as though they were movie stars and publishing photographs of them posing at parties in a back-page feature entitled “Digital Dim Sum.” But those days were over. Calacanis looked at Martesko reprovingly. “Let’s get someone with a job,” he said.

Next on the agenda was the magazine’s annual “Silicon Alley 100” issue, which lists, in order of importance, the people who matter in the Internet business in New York. Calacanis wanted to expand last year’s passport-size snapshots to more glamorous full-page portraits with a small amount of text.

“Whole body or only the head?” Steve Morris, the art director, wanted to know. It was not an idle question. Something had gone wrong with the previous cover’s closeup, and Glenn Meyers, the C.E.O. of the Internet consulting company Rare Medium, had come out looking as though he had been heavily seasoned with paprika.

“They’re ordering a ton of copies,” Calacanis protested when he was reminded of this.

“Yeah, to get them out of circulation.”

Calacanis paused to take this in. The large intern whispered to the small one that he had discovered a Web site named Doodie.com. “It’s the best Web site ever,” he said. “There’s a new poop cartoon every day.”

Next, Calacanis announced with a flourish a plan to publish a coffee-table book of the Silicon Alley crème de la crème-bringing together the top hundred from the “100” lists of the past two years. This idea was greeted with tentative giggling.

“Umm, who exactly is going to buy this book?” one of the editors inquired, after a moment, when it became clear from Calacanis’s face that the idea was not a joke.

“Jeff Dachis, at Razorfish,” Calacanis said. “How many copies do you think he’s going to buy? A thousand!”

More giggling, louder this time. Calacanis raised his arms in self-defense. “I’m serious! He’ll buy a thousand copies and send them to his clients with a Post-it stuck on his page.” But he confessed to his staff that he was anxious about the “100” group photograph. Last year, more than eighty people had assembled in his loft for the picture, but he wondered whether this year the proj-ect was feasible. “Some of those guys are billionaires now,” he mused. “I don’t know if they’ll show up.”

It is generally agreed that it was the “100” list, inaugurated late in 1997, that put Calacanis on the map. No matter what anybody thought of him and his magazine, there was something about a published ranking that carried a potency all its own. Everybody wanted to be on the list, and everybody who made it cared who ranked above and below him. Better still, those who made it tended to note that fact in their publicity material, and this had the effect of bolstering the list’s (and the magazine’s) reputation. There had been new-media awards ceremonies before the list

came out, but they tended to focus on the doomed technology of CD-roms, and they rewarded artistic achievement.

Calacanis’s list rewarded importance, and, for the most part, that meant business. It was not just a matter of money, however. If the list had simply tabulated corporate wealth, it would have been nothing more than an accounting exercise. By measuring importance, it preserved that crucial dimension of mystery and subjectivity which made it productively controversial. “The ‘100’ list creates tremendous resentment,” one Alley figure who’s made it on both times says. “Behind Jason’s back, most people say nasty things about him, but to his face they are nice as nice can be, because to be on the map of New York cyberbusiness they’ve got to be in his ‘100.’ ”

Calacanis knows this, of course, and welcomes it as a sign of clout. “People who don’t get on it probably think I’m a little full of myself, a little drunk with the power of the magazine,” he says, and shrugs. “They feel spurned because I don’t love them, and they think-wrongly-that if I loved them my love would make them successful. God forbid someone should look at himself in the mirror and think, I had a bad idea.”

But the list served a second function, too: it signalled that on lower Broadway, where a minute ago there had been nothing, there were now a hundred new-media people worth writing about. As such, it is a key element of Calacanis’s campaign to convince the world that Silicon Alley is the place in which the new-media business will come gloriously into its own. His argument, which he repeats frequently, is that now, as in the early days of any medium, it is the technology people who make the money and attract the attention, but later on only the creative types, in New York and Los Angeles, will have a hope of inventing the new genres of entertainment and advertising required to arrest the evanescent attentions of the Internet consumer. Calacanis has had limited success in promoting this view. “There are thousands of little guys in New York,” Henry Blodget, an Internet analyst at Merrill Lynch, says. “And they’re little for a reason, which is that content isn’t big business.”

In the early afternoon, Calacanis rode a taxi uptown to the Sheraton on Seventh Avenue, to drop in on a trade show sponsored by Jupiter, an Internet market-research company. He strolled past the exhibits, sampling the atmosphere. “Look how empty this place is,” he said, sotto voce. “My show? Packed.” He wandered over to the beverage stand, poured himself a cup of coffee, looked about in vain for milk, and shook his head genially as though docking points in a game. “My show will be classy,” he pronounced. “We serve wine and mimosas at lunch, and we have sushi. It’s a more mature environment.”

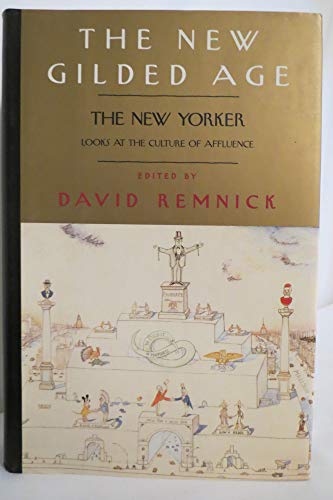

Who are the barons of the new economy? Profiles of Martha Stewart by Joan Didion, Bill Gates by Ken Auletta, and Alan Greenspan by John Cassidy reveal the personal histories of our most influential citizens, people who affect our daily lives even more than we know. Who really understands the Web? Malcolm Gladwell analyzes the economics of e-commerce in "Clicks and Mortar." Profiles of two of the Internet's most respected analysts, George Gilder and Mary Meeker, expose the human factor in hot stocks, declining issues, and the instant fortunes created by an IPO. And in "The Kids in the Conference Room," Nicholas Lemann meets McKinsey & Company's business analysts, the twenty-two-year-olds hired to advise America's CEOs on the future of their business, and the economy.

And what defines this new age, one that was unimaginable even five years ago? Susan Orlean hangs out with one of New York City's busiest real estate brokers ("I Want This Apartment"). A clicking stampede of Manolo Blahniks can be heard in Michael Specter's "High-Heel Heaven." Tony Horwitz visits the little inn in the little town where moguls graze ("The Inn Crowd"). Meghan Daum flees her maxed-out credit cards. Brendan Gill lunches with Brooke Astor at the Metropolitan Club. And Calvin Trillin, in his masterly "Marisa and Jeff," portrays the young and fresh faces of greed.

Eras often begin gradually and end abruptly, and the people who live through extraordinary periods of history do so unaware of the unique qualities of their time. The flappers and tycoons of the 1920s thought the bootleg, and the speculation, would flow perpetually—until October 1929. The shoulder pads and the junk bonds of the 1980s came to feel normal—until October 1987. Read as a whole, The New Gilded Age portrays America, here, today, now—an epoch so exuberant and flush and in thrall of risk that forecasts of its conclusion are dismissed as Luddite brays. Yet under The New Yorker's examination, our current day is ex-posed as a special time in history: affluent and aggressive, prosperous and peaceful, wired and wild, and, ultimately, finite.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurRandom House Inc

- Date d'édition2000

- ISBN 10 0375505415

- ISBN 13 9780375505416

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages432

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 2,99

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The New Gilded Age: The New Yorker Looks at the Culture of Affluence

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0375505415

The New Gilded Age: The New Yorker Looks at the Culture of Affluence

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0375505415

The New Gilded Age: The New Yorker Looks at the Culture of Affluence

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0375505415

The New Gilded Age: The New Yorker Looks at the Culture of Affluence

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new0375505415

THE NEW GILDED AGE: THE NEW YORK

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.65. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0375505415