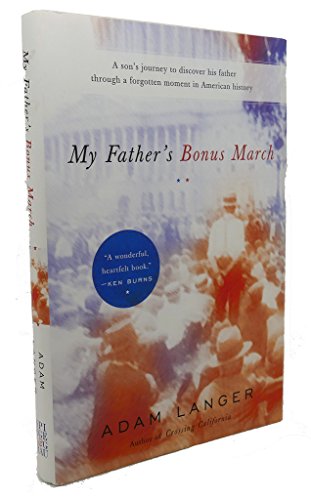

Articles liés à My Father's Bonus March

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNBook by Langer Adam

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

Prologue

Stories I Know

People are so soon gone; let us catch them.

Virginia Woolf, The Waves

2007

My daughter is two years old, and she and I are sitting on the front steps outside my mother’s house on Mozart Street in West Rogers Park on the North Side of Chicago. The sun has long since set and it’s way past Nora’s bedtime, but she shows no sign of falling asleep anytime soon, so I’ve been telling her stories about the neighborhood.

This is the same stoop where I would sit with my dad when he was still alive, I say, the same place where the two of us would watch and greet the neighbors going by—Loping Leemie on his way to the Jewish academy; Mr. Primack with his briefcase, off to work; Rabbi Michael Small, cigar in hand, heading for his shul on California and Albion.

A peaceful neighborhood, I tell Nora, a good place to grow up. In the 1970s, we never locked our doors. When we went out, we wouldn’t even take our house keys along—until the night we returned to find our side door open, the dresser drawers upturned, clothes and papers everywhere. Our lockbox was gone, the one full of silver dollars my mom had received from her mother.

I ask Nora if I should tell her more about this block.

She nods, so I keep going.

Well, I say, see that house across the street, the one that’s a little farther back than the others? An old couple lived there with their motorcycle- riding son, who moved out when I was a kid. When the blizzard of 1979 hit Chicago and the city didn’t plow our streets, everybody on our block except the couple across the street pitched in twenty dollars to hire a private tow-truck driver to shovel. Everything got shoveled except their parking space. Their car just stood there like an igloo on asphalt until the woman sheepishly ran out with her twenty-dollar bill, and then everyone started working together to dig out her car.

As the night grows darker, I tell Nora more little stories about our old neighbors—Mrs. Golnick, who rushed over to our house the moment after she learned hers had been robbed; Sol Zimmerman, who dispatched a dead mouse from our kitchen when my mother and I were too frightened to do it ourselves; Irv Ellis, the onetime high school basketball star; Mr. Joe Small, the one-man neighborhood watch committee; Dr. Friedman, whose sister taught me in Hebrew school; an Orthodox Jewish man who wore shiny black shoes and played catch with me—he told me he used to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

I tell Nora more stories about myself, too. This is the same block where I’d ride up and down on my red tricycle with its Mickey Mouse bell and later on my yellow Schwinn, I tell her, the same block where I’d walk to kindergarten with my pal Beth Goldberg and debate the existence of God. “He’s everywhere!” she’d say. “But how can He be everywhere?” I’d demand.

I say that these are the same steps where I’d play ball-against-the-wall after school with a white rubber ball and a Ron Santo mitt. “Play ball, Adam,” Joe Small would shout whenever he saw me, and when I was done, he’d tell me about the trips he’d taken to Vegas, the appraised Omega watch he’d purchased there with his winnings, the Phyllis Diller show he’d seen. On weekends, my grade school pals and I would play Wiffle ball, making up our own rules—hit my dad’s black Ford, get a ground-rule double; smack the ball over Mr. Small’s red Lincoln, get a home run.

But I don’t know how much Nora understands of what I’m telling her. It’s really late, I finally say; it’s time to go to bed. See, everybody’s lights are off; everyone is asleep. The Friedmans are asleep and the Smalls are asleep and the Seruyas are asleep and the dogs and the cats and the squirrels and the birds are asleep, so maybe we should go to sleep, too.

But Nora says no.

“Okay,” I say. “What do you want to do?”

“More stories, Papa,” Nora says. “Tell more stories.”

And at this moment, I realize that this stoop where my daughter and I are sitting, this street, this neighborhood in this city, this is the place that first made me want to become a writer, listening to our neighbors’ stories, looking at houses and imagining what was going on inside. And at this moment, I realize, too, that this is what I still miss most about my father—the stories he isn’t here to tell me anymore, the stories he never got around to telling me at all. I long to hear the stories about where he grew up, a place he never took me, the stories about his dreams, which he never shared.

“All right,” I say to Nora, “let’s tell more stories.”

CHICAGO (2006)

I

Memories of my father, a brilliant but contradictory man who was so present in my life and yet sometimes so distant and difficult to know, begin to return to me, appropriately enough, when I’m flying twenty thousand feet above the ground, looking down at the city where he and I were both born. It’s wintertime, and I’m sitting in the window seat of a half-empty Embraer RJ-145, flying from Indianapolis to Chicago, where I will board another plane to head to New York. My dad died two months ago, in November, at the age of eighty, and this will be the first time I will ever pass through Chicago without stopping at my parents’ house.

The last plane ride I ever took with both my mom and dad was in 1978, when I was ten; we went to San Francisco for Memorial Day weekend. At the time, little seemed remarkable about our trip—we stayed at the Stanford Court Hotel, dined at Kan’s in Chinatown, watched the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company perform H.M.S. Pinafore, hung out with one of my dad’s old medical school pals, a chatterbox named Stan, who had struck it rich in Australian opal mines and referred to himself in the third person. I wore a brown nubbly suit to meet Stan; he told me I looked like David Copperfield.

But after we returned to Chicago, for more than the next twenty-five years, my father never left the state of Illinois. Sometimes, he’d talk about taking a trip to Williamsburg, Virginia, to view Civil War sites; about driving to Poughkeepsie, New York, to visit me in college, and to West Branch, Iowa, to research a book he’d always wanted to write about the 1932 Bonus March, a historical incident that fascinated him. He talked about taking a plane to London and leaving America for the first time; and one time not all that long ago about flying to Minnesota so that he could find a doctor at the Mayo Clinic who might be able to help him.

But he never went any of those places.

My dad, who rarely seemed to bother with introspection, never talked much about himself to me. He didn’t talk about his inner life, never told me how he felt about flying or why he eventually stopped, but he never seemed to like giving control to anyone else—he boasted about once being on a plane that was taking too long to leave its gate; he insisted the flight attendants open the exit door so that he and my mother could get out, grab their luggage, and go back home. That was the man I knew—doing everything his way, always in a rush. If it couldn’t be done fast, it wasn’t worth doing. He told me that on a trip to Los Angeles before I was born, he and my mom were in the audience of a sitcom and he had had enough of the show.

“You can’t leave, sir,” the usher said.

“Like hell I can’t,” my dad replied.

Yep, that was the dad I knew.

When I close my eyes, I can still easily picture my father. He was a broad-shouldered man, stocky, crew-cutted, and he stood five seven, just about the same height as I am. He wore black or brown dress shoes and Brooks Brothers button-down shirts—white or light blue, pale yellow in the 1970s. He walked with a limp and during the last years of his life, he had considerable difficulty with his knees and hips; still, he always moved fast, as if he was on his way to someplace more important, and if he was ever feeling any pain, save for the occasional moan of “Oy vey,” he wouldn’t let you know about it. His default facial expression split the difference between knowing smirk and dubious sneer, as if he was in on a joke he wouldn’t bother telling you, or as if you’d just told him something but he wasn’t certain he believed you. “I don’t know if I do or I don’t,” he liked to say. “I don’t know if it’s true or it isn’t.” Tough guy to get to know, even if you saw him every day.

Earlier tonight, when this plane took off from Indianapolis, a light snow was falling, but the night is now clear and the plane is flying relatively low; this is a short flight, only about a half hour in the air, and as we begin our approach to O’Hare Airport, I look out my window at the lights of Chicago. My father worked for more than fifty years as a radiologist, and looking at the city below me, I can almost envision an entire X-ray of his life developing—just about every place he ever went is becoming visible through this small window. I can actually make out where he was born, where he grew up, where he lived, where he worked, and where he died. And in everything I can see tonight, in all the lights and in all the blackness, are fragments of stories he told—in my mind, those stories are all the pieces I still have of him.

From this window, I can see Chicago’s old West Side, which was essentially the Jewish ghetto when my dad was born there on March 16, 1925, in Chicago’s Lying-In Hospital, the son of immigrants Rebecca and Samuel Langer. My dad was born with the name Sidney Langer, but he was hospitalized for pneumonia at the age of two and his parents changed hi...

Revue de presse :

Stories I Know

People are so soon gone; let us catch them.

Virginia Woolf, The Waves

2007

My daughter is two years old, and she and I are sitting on the front steps outside my mother’s house on Mozart Street in West Rogers Park on the North Side of Chicago. The sun has long since set and it’s way past Nora’s bedtime, but she shows no sign of falling asleep anytime soon, so I’ve been telling her stories about the neighborhood.

This is the same stoop where I would sit with my dad when he was still alive, I say, the same place where the two of us would watch and greet the neighbors going by—Loping Leemie on his way to the Jewish academy; Mr. Primack with his briefcase, off to work; Rabbi Michael Small, cigar in hand, heading for his shul on California and Albion.

A peaceful neighborhood, I tell Nora, a good place to grow up. In the 1970s, we never locked our doors. When we went out, we wouldn’t even take our house keys along—until the night we returned to find our side door open, the dresser drawers upturned, clothes and papers everywhere. Our lockbox was gone, the one full of silver dollars my mom had received from her mother.

I ask Nora if I should tell her more about this block.

She nods, so I keep going.

Well, I say, see that house across the street, the one that’s a little farther back than the others? An old couple lived there with their motorcycle- riding son, who moved out when I was a kid. When the blizzard of 1979 hit Chicago and the city didn’t plow our streets, everybody on our block except the couple across the street pitched in twenty dollars to hire a private tow-truck driver to shovel. Everything got shoveled except their parking space. Their car just stood there like an igloo on asphalt until the woman sheepishly ran out with her twenty-dollar bill, and then everyone started working together to dig out her car.

As the night grows darker, I tell Nora more little stories about our old neighbors—Mrs. Golnick, who rushed over to our house the moment after she learned hers had been robbed; Sol Zimmerman, who dispatched a dead mouse from our kitchen when my mother and I were too frightened to do it ourselves; Irv Ellis, the onetime high school basketball star; Mr. Joe Small, the one-man neighborhood watch committee; Dr. Friedman, whose sister taught me in Hebrew school; an Orthodox Jewish man who wore shiny black shoes and played catch with me—he told me he used to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

I tell Nora more stories about myself, too. This is the same block where I’d ride up and down on my red tricycle with its Mickey Mouse bell and later on my yellow Schwinn, I tell her, the same block where I’d walk to kindergarten with my pal Beth Goldberg and debate the existence of God. “He’s everywhere!” she’d say. “But how can He be everywhere?” I’d demand.

I say that these are the same steps where I’d play ball-against-the-wall after school with a white rubber ball and a Ron Santo mitt. “Play ball, Adam,” Joe Small would shout whenever he saw me, and when I was done, he’d tell me about the trips he’d taken to Vegas, the appraised Omega watch he’d purchased there with his winnings, the Phyllis Diller show he’d seen. On weekends, my grade school pals and I would play Wiffle ball, making up our own rules—hit my dad’s black Ford, get a ground-rule double; smack the ball over Mr. Small’s red Lincoln, get a home run.

But I don’t know how much Nora understands of what I’m telling her. It’s really late, I finally say; it’s time to go to bed. See, everybody’s lights are off; everyone is asleep. The Friedmans are asleep and the Smalls are asleep and the Seruyas are asleep and the dogs and the cats and the squirrels and the birds are asleep, so maybe we should go to sleep, too.

But Nora says no.

“Okay,” I say. “What do you want to do?”

“More stories, Papa,” Nora says. “Tell more stories.”

And at this moment, I realize that this stoop where my daughter and I are sitting, this street, this neighborhood in this city, this is the place that first made me want to become a writer, listening to our neighbors’ stories, looking at houses and imagining what was going on inside. And at this moment, I realize, too, that this is what I still miss most about my father—the stories he isn’t here to tell me anymore, the stories he never got around to telling me at all. I long to hear the stories about where he grew up, a place he never took me, the stories about his dreams, which he never shared.

“All right,” I say to Nora, “let’s tell more stories.”

CHICAGO (2006)

I

Memories of my father, a brilliant but contradictory man who was so present in my life and yet sometimes so distant and difficult to know, begin to return to me, appropriately enough, when I’m flying twenty thousand feet above the ground, looking down at the city where he and I were both born. It’s wintertime, and I’m sitting in the window seat of a half-empty Embraer RJ-145, flying from Indianapolis to Chicago, where I will board another plane to head to New York. My dad died two months ago, in November, at the age of eighty, and this will be the first time I will ever pass through Chicago without stopping at my parents’ house.

The last plane ride I ever took with both my mom and dad was in 1978, when I was ten; we went to San Francisco for Memorial Day weekend. At the time, little seemed remarkable about our trip—we stayed at the Stanford Court Hotel, dined at Kan’s in Chinatown, watched the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company perform H.M.S. Pinafore, hung out with one of my dad’s old medical school pals, a chatterbox named Stan, who had struck it rich in Australian opal mines and referred to himself in the third person. I wore a brown nubbly suit to meet Stan; he told me I looked like David Copperfield.

But after we returned to Chicago, for more than the next twenty-five years, my father never left the state of Illinois. Sometimes, he’d talk about taking a trip to Williamsburg, Virginia, to view Civil War sites; about driving to Poughkeepsie, New York, to visit me in college, and to West Branch, Iowa, to research a book he’d always wanted to write about the 1932 Bonus March, a historical incident that fascinated him. He talked about taking a plane to London and leaving America for the first time; and one time not all that long ago about flying to Minnesota so that he could find a doctor at the Mayo Clinic who might be able to help him.

But he never went any of those places.

My dad, who rarely seemed to bother with introspection, never talked much about himself to me. He didn’t talk about his inner life, never told me how he felt about flying or why he eventually stopped, but he never seemed to like giving control to anyone else—he boasted about once being on a plane that was taking too long to leave its gate; he insisted the flight attendants open the exit door so that he and my mother could get out, grab their luggage, and go back home. That was the man I knew—doing everything his way, always in a rush. If it couldn’t be done fast, it wasn’t worth doing. He told me that on a trip to Los Angeles before I was born, he and my mom were in the audience of a sitcom and he had had enough of the show.

“You can’t leave, sir,” the usher said.

“Like hell I can’t,” my dad replied.

Yep, that was the dad I knew.

When I close my eyes, I can still easily picture my father. He was a broad-shouldered man, stocky, crew-cutted, and he stood five seven, just about the same height as I am. He wore black or brown dress shoes and Brooks Brothers button-down shirts—white or light blue, pale yellow in the 1970s. He walked with a limp and during the last years of his life, he had considerable difficulty with his knees and hips; still, he always moved fast, as if he was on his way to someplace more important, and if he was ever feeling any pain, save for the occasional moan of “Oy vey,” he wouldn’t let you know about it. His default facial expression split the difference between knowing smirk and dubious sneer, as if he was in on a joke he wouldn’t bother telling you, or as if you’d just told him something but he wasn’t certain he believed you. “I don’t know if I do or I don’t,” he liked to say. “I don’t know if it’s true or it isn’t.” Tough guy to get to know, even if you saw him every day.

Earlier tonight, when this plane took off from Indianapolis, a light snow was falling, but the night is now clear and the plane is flying relatively low; this is a short flight, only about a half hour in the air, and as we begin our approach to O’Hare Airport, I look out my window at the lights of Chicago. My father worked for more than fifty years as a radiologist, and looking at the city below me, I can almost envision an entire X-ray of his life developing—just about every place he ever went is becoming visible through this small window. I can actually make out where he was born, where he grew up, where he lived, where he worked, and where he died. And in everything I can see tonight, in all the lights and in all the blackness, are fragments of stories he told—in my mind, those stories are all the pieces I still have of him.

From this window, I can see Chicago’s old West Side, which was essentially the Jewish ghetto when my dad was born there on March 16, 1925, in Chicago’s Lying-In Hospital, the son of immigrants Rebecca and Samuel Langer. My dad was born with the name Sidney Langer, but he was hospitalized for pneumonia at the age of two and his parents changed hi...

“Chicago’s own bard, Studs Terkel, would be proud, maybe even envious, of Adam Langer’s terrific tale. He weaves American history, his father’s Depression era coming of age, and his own experience growing up in the ’70s and ’80s into a narrative quilt so artful it covers a reader's sensibility with warmth and beauty. This is truly a multigenerational treat.”—Peter Davis, Academy-Award winning directory of Hearts and Minds

“Adam Langer has written a family mystery story that takes the reader back to a complex past, created from other people's recollections and Adam's own pilgrimage to an event hardly touched by American memory.”—Thomas B. Allen, co-author of The Bonus March: An American Epic.

“My Father’s Bonus March is a fascinating and touching book, part personal memoir, part history. Its examination of the Bonus March of 1932 through the eyes of father and son is an extraordinary exhibition of the personal meanings of history.”—Scott Turow, author of Presumed Innocent

“A wonderful, heartfelt book.”—Ken Burns

“At last–a memoir that understands the deepest mission of first person narrator, which is to be a steward of history. Adam Langer’s magnificent documentary work in My Father’s Bonus March is a meticulous reconstruction, part detective story, part elegy, and altogether alluring in its fine attention and relentless search into the Depression and out again. This remarkable book comes to us just when we need it and has an uncanny and haunting resonance for our times.”—Patricia Hampl, author of The Florist’s Daughter

“My Father's Bonus March is a brilliant and beautiful work of memory, a hymn to boyhood, a hymn to Chicago, that somber city, driven by the need that drives all those rare books that you know, on first encountering, you will re-read and cherish–the need to get back what has been lost.”—Rich Cohen, author of Sweet and Low

“A truly fascinating flashback to the Great Depression. My Father's Bonus March is a work of genuine integrity and wise reflection.”—Douglas Brinkley, author of Tour of Duty and The Great Deluge

“Adam Langer has written a family mystery story that takes the reader back to a complex past, created from other people's recollections and Adam's own pilgrimage to an event hardly touched by American memory.”—Thomas B. Allen, co-author of The Bonus March: An American Epic.

“My Father’s Bonus March is a fascinating and touching book, part personal memoir, part history. Its examination of the Bonus March of 1932 through the eyes of father and son is an extraordinary exhibition of the personal meanings of history.”—Scott Turow, author of Presumed Innocent

“A wonderful, heartfelt book.”—Ken Burns

“At last–a memoir that understands the deepest mission of first person narrator, which is to be a steward of history. Adam Langer’s magnificent documentary work in My Father’s Bonus March is a meticulous reconstruction, part detective story, part elegy, and altogether alluring in its fine attention and relentless search into the Depression and out again. This remarkable book comes to us just when we need it and has an uncanny and haunting resonance for our times.”—Patricia Hampl, author of The Florist’s Daughter

“My Father's Bonus March is a brilliant and beautiful work of memory, a hymn to boyhood, a hymn to Chicago, that somber city, driven by the need that drives all those rare books that you know, on first encountering, you will re-read and cherish–the need to get back what has been lost.”—Rich Cohen, author of Sweet and Low

“A truly fascinating flashback to the Great Depression. My Father's Bonus March is a work of genuine integrity and wise reflection.”—Douglas Brinkley, author of Tour of Duty and The Great Deluge

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurSpiegel & Grau

- Date d'édition2009

- ISBN 10 0385523726

- ISBN 13 9780385523721

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages243

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 56,36

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

My Father's Bonus March

Edité par

Spiegel & Grau

(2009)

ISBN 10 : 0385523726

ISBN 13 : 9780385523721

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks35519

Acheter neuf

EUR 56,36

Autre devise

MY FATHER'S BONUS MARCH

Edité par

Spiegel & Grau

(2009)

ISBN 10 : 0385523726

ISBN 13 : 9780385523721

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.35. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0385523726

Acheter neuf

EUR 73,03

Autre devise