Articles liés à The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNMy mother was born in Ireland as Margaret Murphy, but everyone called her Peg. She never used her married name, Mrs. John Freely, always identifying herself as Peg Murphy. This was not uncommon among the Irish women of her time, but it was mostly her fierce spirit of independence that made her keep her own name, for she was Peg Murphy and not Mrs. Somebody Else, she always said. We were led by her to believe that she had been born in 1904, but I learned many years later that her true date of birth was 1897. I never found out why she subtracted seven years from her age. Perhaps it was to be eternally young, for she often spoke of going off to Tir na nÓg, the “land of the heart’s desire,” where in Celtic myth no one grows old. So Peg told me one day. Many years later I read Eavan Boland’s numinous rendering of this whispered promise:

Fair woman, will you come with me

to a wondrous land where there is music?

Hair is like the blossoming primrose there;

smooth bodies are the color of snow

There, there is neither mine nor yours;

bright are teeth, dark are brows,

A delight to the eye the number of our hosts,

the color of fox-glove every cheek.

She was one of eleven children, all but one of whom left Ireland and emigrated to the United States. They were helped by relatives in Lawrence, Massachusetts, from an earlier family migration. Her paternal grandfather had “died on the roads” when he and his family were evicted from their home in the last years of the Great Hunger, after which his widow and surviving children had emigrated to America and found refuge in Lawrence. But her eldest son, Peg’s father, Tómas Murphy, had not taken to life in America and returned to Ireland, though none of his family was left there.

Tómas was born in County Kerry on the Dingle Peninsula, which together with the Kenmare Peninsula to its south forms the southwesternmost extension of Ireland. When Tómas returned from America he found work as a porter for the Irish Railways, on the narrow-gauge line that operated between Tralee, capital of County Kerry, and Dingle, the main town on the peninsula. At the beginning of his first day of work an English tourist, getting on at Tralee, pointed out his trunk on the platform and arrogantly ordered Tómas to put it up on the luggage rack. “Put it up yourself,” said Tómas proudly, walking away to help an old Irishwoman board the train. The conductor, observing this, said, “Murphy, you will not grow gray in the service of the Irish Railways.”

Tómas kept the job for about a year, but then he was dismissed for giving another English tourist a piece of his mind about Britain’s treatment of Ireland. It was just as well that he left, for the following Whitsunday there was a terrible accident on the Tralee–Dingle line. Locomotive Number One swerved off the tracks on the Curraduff Bridge and fell thirty feet into the river, killing the engineer, the conductor, the porter, and ninety pigs, who were the only passengers that day. An old woman in Dingle remarked to Tómas that he had been spared by the hand of God, to which he responded, according to Peg, “I’m sure the Almighty had more important matters to think about that day than the fate of three Irishmen and ninety pigs.”

Soon afterward Tómas met and fell in love with a pretty young schoolteacher named Maire Ashe, whose father was the postmaster in Anascaul, the only town of any size between Tralee and Dingle. Tómas and Maire married and settled down in a tiny cottage by the sea four miles east of Inch, the enormous transverse sand cape on the south coast of the Dingle Peninsula. Tómas became a fisherman, making himself a small currach, a wickerwork boat covered with tarred canvas. He also built a little dock to moor his currach, in a cove below his cottage, that is still called Murphy’s Landing. On the hillside behind the cottage he cleared and walled in a small plot of land and planted it with potatoes, cabbage, barley, and hay, building a small barn that sheltered a cow, a donkey, and a score of chickens. He farmed his little plot and at intervals set his nets and lines for codfish and herring in Dingle Bay, searching the rocky strand at low tide for periwinkles and mussels. With these resources, Tómas and Maire raised eleven children, five of them boys and six girls, all of whom survived their childhood, something of a miracle in rural Ireland at the time.

The Murphy children learned reading, writing, arithmetic, and not much more at the Kerry district school, a two-room schoolhouse three miles west along the coast from where they lived, making the journey barefoot in all seasons. Their schoolmaster was named Daniel Quill, whom Peg always referred to as an “ignorant tyrant.” Once he announced that there would be no school the following day, for it was the Feast of the Circumcision. Peg, who was then about eleven, raised her hand and asked, “What is circumcision?” Master Quill called her up in front of the class, and then with all of his might slapped her across the face, knocking her down. She later said that there were two possible reasons for Master Quill’s violent response: one was that he knew what circumcision was, and the other was that he did not—but either way he would have been driven to rage by his embarrassment.

The other figure of authority in Inch was the local Catholic priest, Father Mulcahey, whom Peg hated as much as she loathed Master Quill. One rainy winter day she was walking home from school, barefoot as always, accompanied by a classmate, the daughter of a neighbor who was prosperous enough to buy shoes for his children. Father Mulcahey was driving their way in his horse and carriage, but when he stopped he offered a lift to the other girl but not to Peg, who was left to walk home three miles alone in the freezing rain, consumed with a bitter rage that welled up again in her later life whenever she told the story. I often wondered whether that incident was the root of Peg’s atheism, for although she sent us to Catholic schools she never once went to church herself. When her granddaughter Maureen graduated from Harvard, Peg, who was then nearly eighty, interrupted Derek Bok, the university president, when he mentioned the name of God in his address, to shout out in her melodious Irish brogue that “God should be abolished!”

The Murphy children all left school in turn after four or five years and went to work, usually on their own farm or those of their neighbors. Peg found a place at Foley’s Public House at Inch, where she looked after the publican’s infant son, Jerry, and also helped out in the bar. She gave part of her wages to her parents, and saved the rest in the hope that she would eventually have enough money to go off to America, the dream of every young person in rural Ireland at the time, for their homeland had nothing to offer them.

Peg was the only one of the children to inherit their mother’s love of reading. Her mother, Maire, had been sent to a convent school by her father, Thomas Ashe, who had been appointed postmaster of Anascaul after he returned from the Crimean War, in which he had served in the British Army. He had been badly wounded in the last battle of the war, the attack on the Redan, and had recuperated in Florence Nightingale’s hospital on the Asian side of the Bosphorus across from Constantinople. He was illiterate when he joined the 88th Regiment of Foot at the age of seventeen years and nine months, but while he was in the British Army he seems to have learned how to read and write, as well as to speak English, which qualified him to serve as postmaster in Anascaul when he returned to Ireland. Maire taught school for a few years before her marriage to Tómas, who was illiterate. (I discovered this only many years later when I first saw Peg’s birth certificate, where her father’s signature appeared as a scrawled X.)

All but one of the children went off in turn to America. Peg was the sixth to leave, after her sisters Hannah, Bea, Annie, Mary, and Nell, with her brothers Jerry, Tommy, Mauris, and Gene following soon afterward. Her younger brother John was the only one who remained at home with Tómas and Maire, helping to look after their farm, which, tiny though it was, still required a lot of manual labor. He too would have gone to America, but he had consumption, which they now call tuberculosis, or so Peg told me.

Peg had saved enough money from her wages at Foley’s to pay for her passage to the United States in steerage, and she had put aside a bit to buy her first pair of shoes, but the friends who emigrated with her went barefoot. The same thing was happening all over Ireland, as the Irish once again left their native land, just as they had during and after the Great Hunger of the mid-nineteenth century.

The story was much the same in the cottage where my father was born, near the town of Ballyhaunis in County Mayo, in the northwest of Ireland. All the Freelys in the world come from in and around Ballyhaunis, the descendants of an O’Friel who moved there from County Donegal in the north around 1800, the date of the thatched cottage in which my father was born. O’Friel was illiterate, and in registering his name the English authorities had written it down as Freely. Otherwise, like most Irish of the soil, the Freelys were a family without a history, just a succession of simple farmers, who at least owned their own plot of land. This is why they survived the Great Hunger, when tenants were evicted and either “died on the roads” or emigrated, diminishing the population of Ireland from eight million to four million in just a decade.

My father, John, was uncertain about the date of his birth. He always said that he had been born the “year of the great wind,” which he thought was 1898, but eventually we learned that he, like my mother, was born in 1897. Neither he nor Peg knew the day on which they were born, so we assigned them birthdays: August 4 for Peg, July 1 for John, to make him a bit older than her. He was the second of the nine children of Michael and Ellen Freely, who had eight boys and one girl: Jim, John, Willie, Tom, Pat, Mike, Charlie, Mary, and Luke. All nine emigrated from Ireland, some to England but most of them to America. Jim, the eldest, eventually returned with his wife, Agnes, to run the family farm after the death of his parents.

There were no books in the house, for Michael and Ellen had never gone to school and were illiterate. Their children went to school up to the age of twelve or so, but since there was no public library in Ballyhaunis they never developed the habit of reading. Thus Peg could never talk to John about literature, nor to anyone else among our relatives and friends, which was one of the reasons she looked down upon Irish immigrants and did not want to live among them—another reason being their addiction to drink.

John left home in the spring of 1916, along with his younger brother Willie, hoping to find work in England. They had not tuppence between them when they decided to leave, as John told me many years later. The only cash in the house was their mother’s “egg money,” a few pennies that she had accumulated by selling eggs now and then when she went to the weekly market in Ballyhaunis. One morning, well before dawn, John awoke and dressed quietly, waking Willie, and went to the cupboard and took his mother’s egg money, vowing to replace it as soon as he found work in England. Then they left the cottage and headed for Ballyhaunis, five miles distant, to catch the weekly train that stopped there at six in the morning. They cut across the fields to intercept the train a mile or so before it reached the town, and when they saw it approaching they stepped out on the track to flag it down. The train stopped for them and the conductor let them come aboard, for he was from Ballyhaunis and knew the family. He didn’t bother to ask them for their tickets, for he knew they wouldn’t have been able to pay for them.

The train had two cars, one for mail and the other for passengers. The seats were all taken, so John and Willie sat down on the floor at the back, covering their faces when the train stopped at Ballyhaunis so they wouldn’t be recognized by anyone who might come aboard there. But no one did, and after the mail was loaded the train chugged off, just as the sun rose over the hills of Roscommon, the next county to the east. Then Willie went to sleep, while John took one last look at Ballyhaunis, which he would never see again. It was Easter Sunday, and he could hear the church bell tolling for the first mass of the day. He blessed himself, and then he too fell asleep.

A while later, the other passengers in the car began waking up, and some of them in the back seats started talking to John and Willie. It turned out that all of them were Irish sailors who had been aboard a British freighter that had been sunk by a German submarine off the northwest coast of Ireland. They had come ashore in lifeboats and were put on the first train leaving for Dublin. They had been given their full pay, and when they were all awake they took up a collection and gave John and Willie enough money to buy shoes and tide them over till they could find work. Pint bottles of Irish whiskey were passed around, and it was then that John had his first taste of hard drink, which started him on the “downward path to ruination,” as Peg would later say.

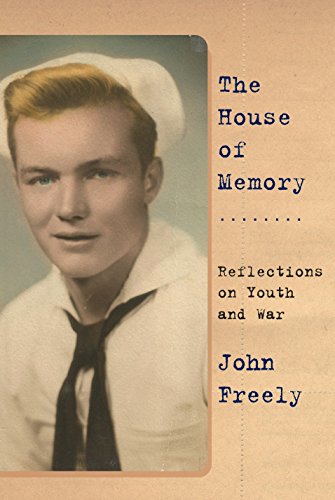

“When young John Freely asked his mother if they belonged to the working class, she answered, ‘We would indeed be of the working class if your father could find steady work.’ Mr. Freely was born in 1926, the son of two Irish immigrants struggling to gain a toehold in Brooklyn . . . The nonagenarian author’s account of the first quarter of his life might be considered his contribution to the canon of the impoverished Irish, though life would soon carry him far from his upbringing . . . Mr. Freely volunteered [to the Navy in 1944] and was placed in ‘Amphibious Roger Three,’ a Navy unit that was being sent to China to train elite forces in the armies of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek . . . In “The House of Memory,” Mr. Freely has provided an account of how a world at war transformed the fate even of those who barely saw action.” —Gregory Crouch, The Wall Street Journal

"The nonagenarian author of scores of books about travel and history returns with a memoir about his boyhood, youth, and World War II. Freely displays an unusually precise memory . . . Such specificity adds an almost surreal clarity to the text." —Kirkus Reviews

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurKnopf Publishing Group

- Date d'édition2017

- ISBN 10 0451494709

- ISBN 13 9780451494702

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages272

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 4,15

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Etat de la jaquette : New. First Edition, First Printing. This is a new hardcover first edition, first printing copy in a new mylar protected DJ, grayish spine. Review slip laid in. N° de réf. du vendeur 077954

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ00D2OW_ns

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 5AUZZZ001A7K_ns

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

Description du livre hardcover. Etat : New. May have light shelf wear from storage. N° de réf. du vendeur 240423060

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks177968

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : Brand New. 320 pages. 8.25x5.63x0.88 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur 0451494709