Articles liés à The Navigator of New York

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

In 1881, Aunt Daphne said, not long after my first birthday, my father told the family that he had signed on with the Hopedale Mission, which was run by Moravians to improve the lives of Eskimos in Labrador. His plan, for the next six months, was to travel the coast of Labrador as an outport doctor. He said that no matter what, he would always be an Anglican. But it was his becoming a fool, not a Moravian, that most concerned his family.

In what little time they had before he was due to leave, they, my mother and the Steads, including Edward, tried to talk him out of it. They could not counter his reasons for going, for he gave none. He would not counter the reasons they gave for why he should stay, instead meeting their every argument with silence. It would be disgraceful, Mother Stead told him; him off most of the time like the men who worked the boats, except that they at least sent home for the upkeep of their families what little money they didn’t spend on booze. This was not how a man born into a family of standing, and married into one, should conduct himself. Sometimes, on the invitation of Mother Stead, a minister would come by and join them in dressing down my father. He endured it all in silence for a while, then excused himself and went upstairs to his study. It was as though he was already gone, already remote from us.

Perhaps the idea to become an explorer occurred to him only after he became an outport doctor. Or he might have met explorers or heard about some while travelling in Labrador. I’m not sure.

At any rate, he had been with the Hopedale Mission just over a year, was at home after his second six-month stint, when he answered an ad he saw in an American newspaper. Applying for the position of ship’s doctor on his first polar expedition, he wrote: “I have for several years now been pursuing an occupation that required arduous travel to remote places and long stretches of time away from home.” Several years, not one. He said that for would-be expeditionaries, such embellishments were commonplace.

He signed on with his first expedition in 1882. A ship from Boston bound for what he simply called “the North” put in at St. John’s to take him on.

First a missionary, now an explorer. And him with a wife and a two-year-old son, and a brother whose lifetime partner he had pledged to be. My aunt’s husband, my uncle Edward.

Father Stead had been a doctor, and it was his wish, which they obliged, that his two sons “share a shingle” with him. My father, older by a year, deferred his acceptance at Edinburgh so that he and Uncle Edward could enrol together. The brothers Stead came back the Doctors Stead in 1876. In St. John’s, Anglicans went to Anglican doctors, whose numbers swelled to nine after the return home of Edward and my father. On the family shingle were listed one-third of the Anglican doctors in the city. It read, “Dr. A. Stead, Dr. F. Stead and Dr. E. Stead, General Practitioners and Surgeons,” as if Stead was not a name, but the initials of some credential they had all earned, some society of physicians to which all of them had been admitted.

Three years after their graduation from Edinburgh, Father Stead died, but the shingle was not altered. Until his death, the two brothers had shared a waiting room, but afterwards my father moved into his father’s surgery, across the hall. From the door that had borne both brothers’ names, my father’s was removed. It was necessary to make only one small change to the green-frosted window of grandfather’s door: the intial A was removed and the initial F put in its place. F for Francis.

Even without Father Stead, the family practice thrived. When asked who their doctor was, people said “the Steads,” as if my father and Edward did everything in tandem: examinations, diagnoses, treatments. When they arrived at reception, new patients were not asked which of the brothers they wished to see -- nor, in most cases, did they arrive with their minds made up. Patients were assigned on an alternating basis. To swear by one of the brothers Stead was to swear by the other.

But with the departure of my grandfather, the Steads were no longer the Steads, and for a while the practice faltered. And no wonder, Edward said, what with one of them having gone off, apparently preferring first the company of Eskimos and Moravians to that of his own kind, and now the profession of nursemaid to a boatload of social misfits to that of doctor. If one of them would do that, what might the other do?

The family itself dropped a notch in the estimation of its peers. It was as if some latent flaw in the Stead character had shown itself at last. My father’s patients did not go across the hall to Edward. They went to other doctors. Some of Edward’s patients did likewise. He had no choice but to accept new ones from a lower social circle.

My father, in letters home, insisted that he would take up his practice again one day. He promised Edward he would pay him the rent that his premises would have fetched from another doctor, but he was unable to make good on the promise, having forsaken all income.

Rather than find another partner, rather than take down the family shingle and replace it with one that bore a stranger’s name, Edward left my father’s office, and everything in it, exactly as it was.

That door. The door of the doctor who was never in but which still bore his name. It must have seemed to his patients that Edward was caught up in some unreasonably protracted period of mourning for his absent brother whose effects he could not bear to rearrange, let alone part with. Every day that door, his brother’s name, the frosted dark green glass bearing all the letters his did except for one. He could not come or go and not be prompted by that door to think of Francis.

The expedition “to the North” he said, immeasurably improved the map of the world, adding to it three small, unpopulated islands.

Soon, my father’s life was measured out in expeditions. When he came back from one, it was weeks before he no longer had to ask what month or what day of the week it was. He would go to his office, turn upside down the stack of newspapers left there for him by Edward and read about what had happened in the world while he was absent from it. He searched out what had been written about the expeditions he had served on, the records they had set. As my father had yet to command an expedition, none of these records was attributed to him. Rarely, these records were some “first” or “farthest.” But most of them were records of endurance, feats made necessary by catastrophes, blunders, mishaps. Declaring a record was usually a way of putting the best face on failure. “First to winter north of latitude . . .” was a euphemism for “Polar party stranded for months after ship trapped in ice off Greenland.”

He graduated with a BA (Hons) in English from Memorial University of Newfoundland, and worked from 1979 to 1981 as a reporter at the St. John's Daily News. Being a reporter was a crash course in how society works, but he realized he didn’t want it as a career. “I’m not that outgoing of a person and you have to be in order to be a good reporter.” He moved away from Newfoundland, firstly to Ottawa, and took up the writing of fiction full-time. In 1983 he graduated with an MA from the University of New Brunswick. His first book, The Story of Bobby O’Malley, was published shortly after, and won the W.H.Smith/Books in Canada First Novel Award. He followed this success two years later with The Time of Their Lives, which won the Canadian Authors' Association Award for Most Promising Young Writer.

His third novel, The Divine Ryans, again a portrait of Irish Catholic Newfoundland, centres on a nine-year-old hockey fanatic, whose father dies and whose family goes to live with relatives who once had money but are fast declining. Time Out has called it “achingly funny, needle sharp...with heart, soul and brains”. One of Johnston’s most comic novels, it earned him the title of ‘the Roddy Doyle of Canada’. The Divine Ryans won the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Prize and has been adapted into a film starring Oscar-nominated actor Pete Postlethwaite. Johnston wrote the screenplay himself for this and also for the adaptation of his next novel, Human Amusements, also optioned for film.

The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Johnston’s fifth novel, in 1998 was shortlisted for the most prestigious fiction awards in Canada, the Governor General's Award and the Giller Prize, the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour and the Rogers Communication Writers Trust Fiction Prize; it won the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Prize and the Canadian Authors Association Award for Fiction. A glowing New York Times Book Review cover story caused the book to leap to the upper ranks of the Amazon.com top 100 selling books of the day. It has been called a ‘Dickensian romp of a novel’, which uses the career of Newfoundland's first premier to create a love story and a tragi-comic elegy to an impossible country.

Published across North America and Europe in several languages, the novel caused some controversy in Canada among those who recalled the real Joey Smallwood, a man who was hated by many Newfoundlanders, including Johnston’s own family, for bringing the island into Canada. Although his strongly anti-confederate family could barely bring themselves to mention Smallwood’s name, Johnston read a biography of the politician when he was 14.

Johnston considered carefully the different ways of establishing ‘fictional/historical plausibility’ in the novel. Re-reading Don Delillo's novel Libra, he observed how “Delillo gave himself the freedom to invent scenes, incidents, conversations as long as they seemed plausible within the fictional world that he created.” He also considered Salman Rushdie’s Midnight's Children, where, in spite of the magic realism, India still gains independence in 1948, and political figures are elected or assassinated under the same circumstances as their real-life counterparts. He decided he would not change or omit anything that was publicly known. “I would fill in the historical record in a way that could have been true, and flesh out and dramatize events that, though publicly known, were not recorded in detail. Most importantly, I would invent for Smallwood a lover/nemesis (Sheilagh Fielding) who could have existed (but didn't) and wove her and Smallwood's story into the history of Newfoundland. This would be my plausibility contract with the reader.”

In 1999 he published Baltimore's Mansion, his first non-fiction book, a family memoir that also became a national bestseller and won the inaugural Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction. Johnston uses the stories of his own childhood and his father and grandfather to cast light on Newfoundland’s struggle over relinquishing independence in 1949. A National Post reviewer concluded that it was a ‘non-fiction novel’ drawing on all Johnston’s narrative powers to “shape the materials of real life into a work of astonishing beauty and power”. In another review, Quill and Quire said “I began to smell the smells, hear the lilt, and experience a sense of the fierce attachment Newfoundlanders feel to their home province no matter where they live,” commenting that Newfoundland geography, history and culture permeates Johnston’s books.

Johnston has lived in Toronto since 1989, although he has to date written exclusively about Newfoundland. “I couldn't write about the island while I was there,” he says. “Life was too immediate. I was too inundated by the place and its details. I'd write about something and see it when I walked across the street the next day.” A “benign homesickness” has become a kind of fuel for writing about the island. He talks of Newfoundland as being too “overwhelmingly beautiful and substantial” to capture. To write with any kind of objectivity, "I need distance to get that sense of what is important and what is significant and what is not."

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurAlfred A. Knopf

- Date d'édition2002

- ISBN 10 0676975321

- ISBN 13 9780676975321

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages496

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 5,10

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

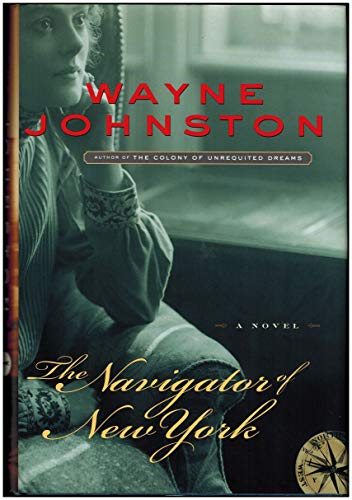

THE NAVIGATOR OF NEW YORK

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.9. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0676975321

The Navigator of New York

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.9. N° de réf. du vendeur 0676975321-2-1

The Navigator of New York

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.9. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0676975321-new